Deep as first love, and wild with regret; O Death in Life, the days that are no more Alfred Tennyson, poet 1809-1892, The Princess (1847)

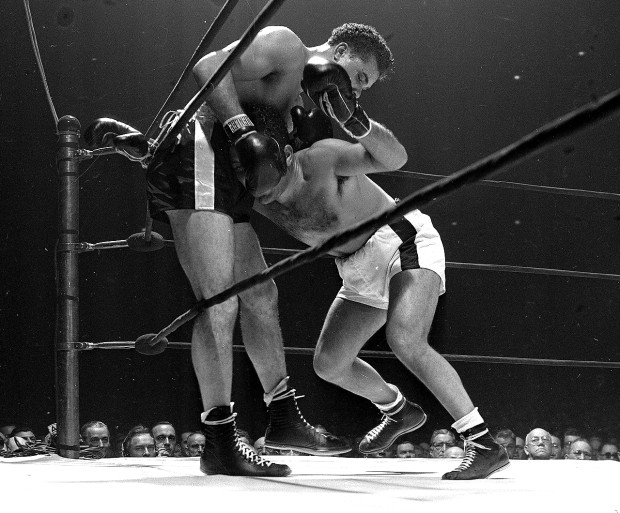

No hush fell beneath the domed ceiling of the Miami Coliseum on New Year’s Eve 1952. Drawn to party, the event, the crowd seemed neither stunned nor charged by the sight of former Middleweight champion and boxing superstar Jake LaMotta slumped to the canvas for the first time in his then 103-fight career. Referee Bill Regan, a Welterweight now broadened by twenty years of retirement, took up the count. LaMotta, 31 and fighting at a career high of 173 pounds, pawed for the bottom rope with his right hand as Regan loomed in.

Opponent Danny Nardico rushed to a corner, the adrenaline racing through his body. The enormity of what he’d just done with a thunderous cross-cum-hook, the last of a flurry of clubbing shots, writ large before him.

If he mouthed through his gum-shield; “stay-down“, it was never reported. His eyes, and those in the half-light beyond the ropes were focussed on LaMotta, the man who had once beaten Sugar Ray Robinson, but now desperate and fumbling for the second rope, his spatial awareness scrambled by fatigue and the weight of the shots that had put him there.

Regan’s fingers splayed wide in front of the bruised fudge of the fallen champion’s face, “FIVE, SIX!“. LaMotta’s right glove, short-cuffed and glistening like a ball of hot tar, found the salvation of the rope. Regan whispered something unknown in LaMotta’s left ear between the metronome of his public voice; “SEVEN, EIGHT!”. Nardico glanced to his corner for reassurance, his own senses under assault too. The laconic, darkened lids of trainer Bill Gore blinked slowly, his face otherwise expressionless. Gore’s experience with all-time greats Willie Pep and Joe Brown, and a hundred other pugs, helping him resist the contagion of excitement that had begun to course through the 3,318 who had bought a ticket.

Gore and Nardico turned back to Regan, the drape of his up-turned slacks swaying with the motion of his exaggerated count; “N-I-I-I-NE!“. LaMotta, as he had stubbornly remained for every other moment of a long professional career, and a second life mainly spent parabolising the first from behind a microphone, was vertical. Standing.

Nardico resumed. Doing what he always did, swinging hard and frequently. His tort, muscular frame appeared to grow, casting an ever greater shadow across the ring, LaMotta ageing and wilting before him. Nardico, younger, fresher, and the bigger man, poured on the pressure. LaMotta held on to the top rope for balance and anchor, a tired ship seeking harbour in the storm. The wiles of a century of bouts compressed into a single act.

Regan danced beside them whilst the twin sets and skewed ties of a night out in 1950s Miami were now engaged and cheering on the local slugger. Immersed in his search for the definitive blow. A bloodlust gripped the crowd, as it always has from the time of Sullivan to the present day. It is a timeless experience, engulfed by the moment, the crowd high on bearing witness to a type of legalised barbarity and with their innate empathy drowned by the alcohol of a balmy New Year’s Eve.

Somehow, by instinct, by habit, by shear bloody-mindedness LaMotta survived the onslaught. He trudged back to his corner, head stooped into the rush of pain Nardico’s blows had inflicted and the head wind of a retirement yet to come. Surrounded by those who knew him best, some of whom cared for the young, old man, and perhaps entirely at his own behest, LaMotta decided to remain on his stool. Regan hovered, dark rings of labour seeping beneath his arms, a Bryllcreemed widow’s peak resisting the glare of the bulbs above, as LaMotta’s surrender became clear.

The fight was over, sinking into the record books as the last chapter in LaMotta’s career as a contender. Nardico danced to the centre ring, the victor, his cornermen danced with him, their disbelief veiled by a shared euphoria. Gore remained outside the ropes, accounting for the accoutrements of battle as those uncomfortable with the spotlight often do. For Nardico, aged 27, ranked 5th in the world even before this win, a shot at Archie Moore for the Light-Heavyweight title would be his reward.

Boxing, as LaMotta could attest, isn’t the simplistic business it appears and Nardico never did get to fight The Ole Mongoose, perhaps fortuitously given the wily champion’s knockout record. Nardico would lose to the lesser Joey Maxim the following March. The momentum Nardico held the night he beat the Bronx Bull was never regained and he retired just four years later with a creditable record of 50-13-4. The last bout of which was little more than an exhibition against a debutant, two and half years after the last of his 13 losses in 1954. In truth, the victor was also retired within 18 months of his best win. Barely 30 years old. It was a different time.

LaMotta would wander, somewhat nomadically, from the blood-soaked canvas to the bright neon and red carpets of the entertainment world. His story is much told and all too often with the omission of the night he faced Danny Nardico on the outskirts of Miami on New Year’s Eve in 1952.

Nardico may never have toppled Archie Moore given a handful of chances but there is a sadness that the promised opportunity never materialised. One LaMotta would almost certainly have been extended had he found a way to fend off the former Marine and his own battle with age and inactivity 70 years ago. It was an era of who you knew, not what you knew. Or perhaps, more accurately, then as now, it was what your name was worth.

The sense of injustice of the fallen champion’s story grew in the retelling. Perhaps unjustly. It was a narrative Martin Scorsese and Robert DeNiro built on. One of numerous motifs present within Jake’s life, not least, his pride in never having been dropped by Sugar Ray Robinson, or anyone else, in a career packed with blood, pain, violence and humour. His impact on others was also explicitly explored.

Despite his frustration, Nardico led a fulfilling life beyond boxing and would frequently relay that the horrors of World War II, in which he was awarded two Purple Hearts and a Silver Star at the age of 18 for, “brave actions while serving as a squad leader in a Marine rifle platoon on Okinawa Shima, Ryukyu Islands on May 2, 1945” ensured everything else he would face in life, including the once irresistible Jake LaMotta, was a “cakewalk“.

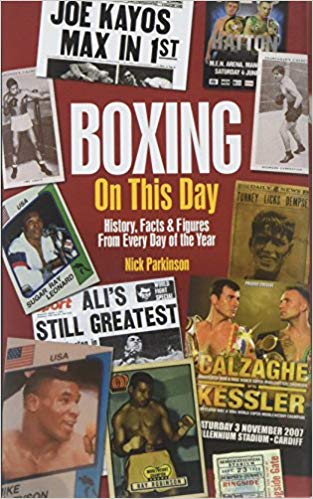

NOTE: The inspiration for this exploration of this bout came from Nick Parkinson’s excellent book Boxing On This Day. At £9.99 it retells a notable boxing tale for every day of the calendar year, I’d recommend it as a superb companion for the boxing fan. Nick can also be found telling this particular story at ESPN.com